Atlas Trekking, Part 2: Summiting Mt. Toubkal

Last January, I started formulating my trip to Morocco as I was finishing two months in Nepal, and hiking big mountains was a priority. The Atlas Mountains may not rival the Himalaya in grandeur or elevation, but they are spectacular, and the hiking offer no shortage of trekking routes. But, not so much in winter. Still, I was thrilled to finally meet this goal in late March, near the end of my time in Morocco: climbing Jebel Toubkal, North Africa's highest summit at 4,165 meters/13,745 feet.

When I first started nosing around for advice on hiking Mount Toubkal, a friend who had recently done it suggested, "It'll help if you know how to use crampons and an ice axe." I didn't. But now I was DEFINITELY not letting go of this goal. Crampons? Ice axes? Heck, yes!

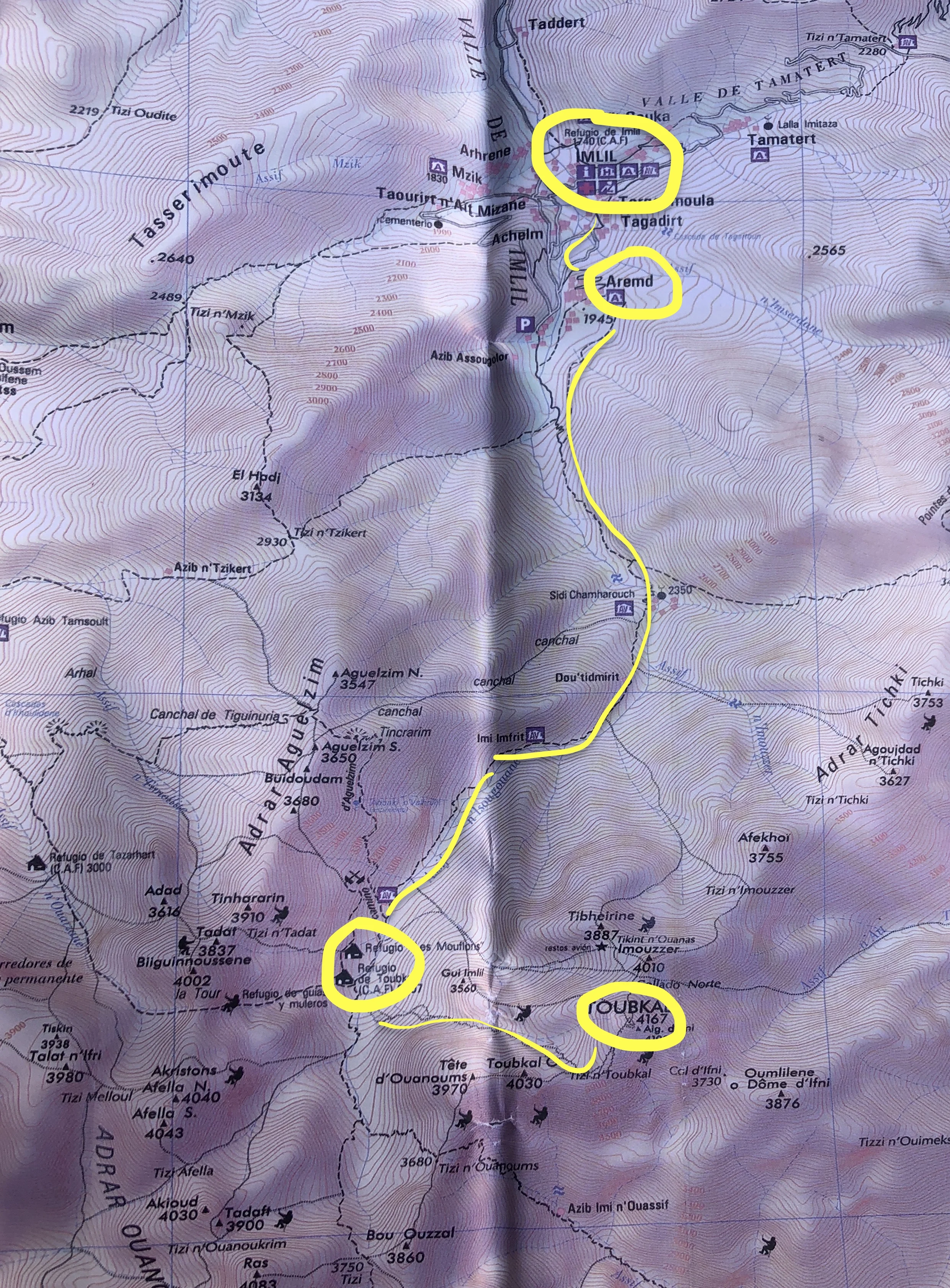

Cold and snow limit the distance and days of guided hikes around Toubkal in March, so I took the speedy two-day option. We were a small group: just me, Tayla and Tom (a British couple with a little mountain experience but plenty fit and full of affable gumption) and our guide Youssef. The route was pretty standard: mid-morning start on Day 1 from Imlil and through Aroumd, late afternoon arrival at the refugios at the base of Toubkal; pre-dawn start on Day 2 from the refugio, to the summit, back to the refugio, back to Imlil. Roundtrip about 26 miles, most of which we covered during the tiring-but-inspiring effort on Day 2.

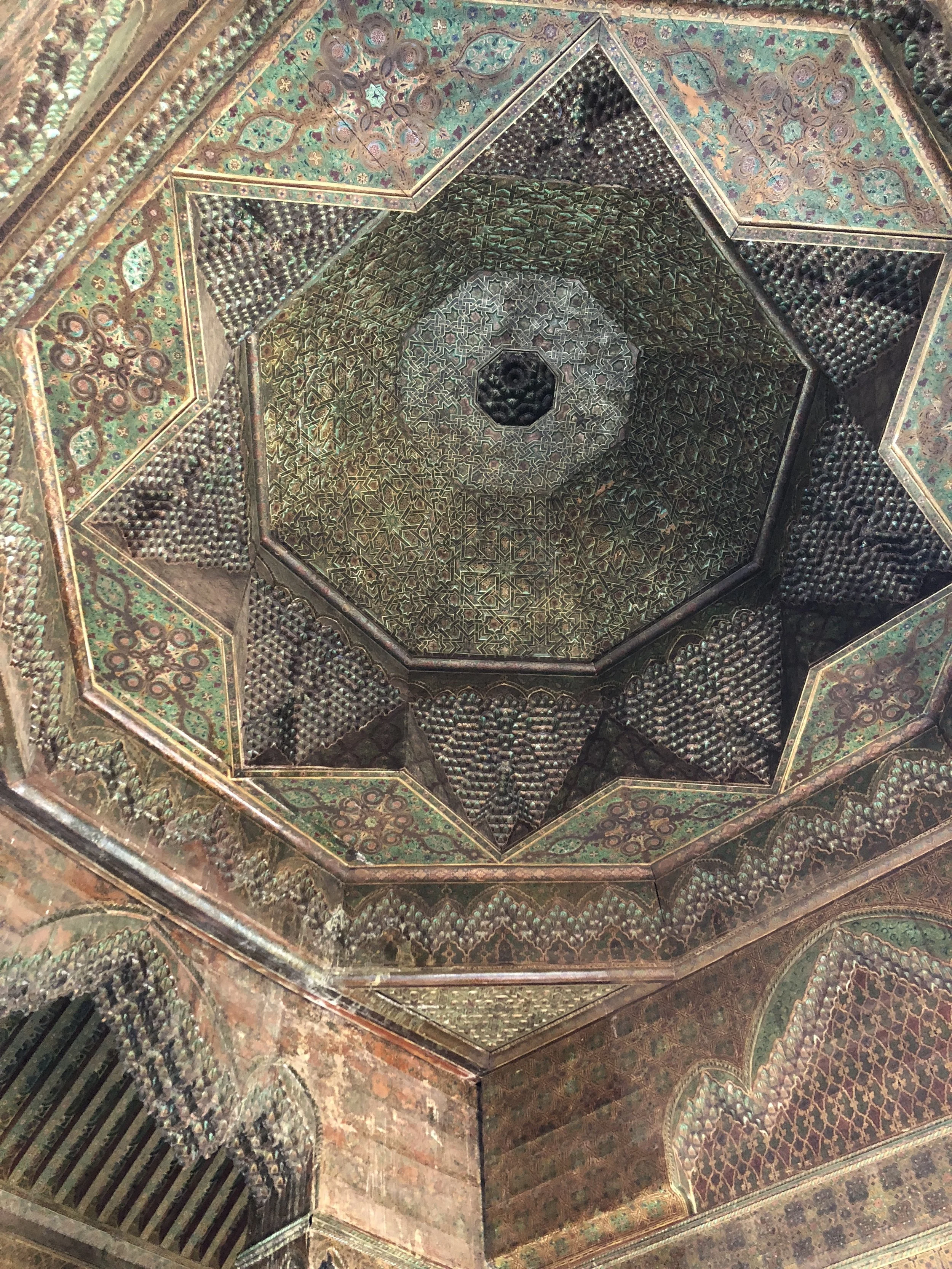

The changes in terrain from Imlil (1,740 meters/4,532 feet) to Toubkal (4,165 meters/13,745 feet) are dramatic, and leave you with a satisfaction that you're covering a significant distance. As in my previous Atlas trek, our packs went ahead with a muleteer and we walked without burden on the trail from Imlil to the lovely village of Aroumd not far up the valley. We stopped there for a tea break at Youssef's family's house (Tayla, Tom and I had tea and took in the view of walnut trees and the mountains up ahead, while Youssef quickly gathered his gear for the trek).

Warm, dry air and blue skies prevailed and made dressing in layers a clutch strategy for the hike. We were roasting in the sun before too long, climbing first along the eastern flank of the valley wall, and then crossing the river to continue upward along the western side of the valley. Juniper shrubs, goats, pack-laden donkeys, long views up and down the valley -- the walk was utterly enjoyable.

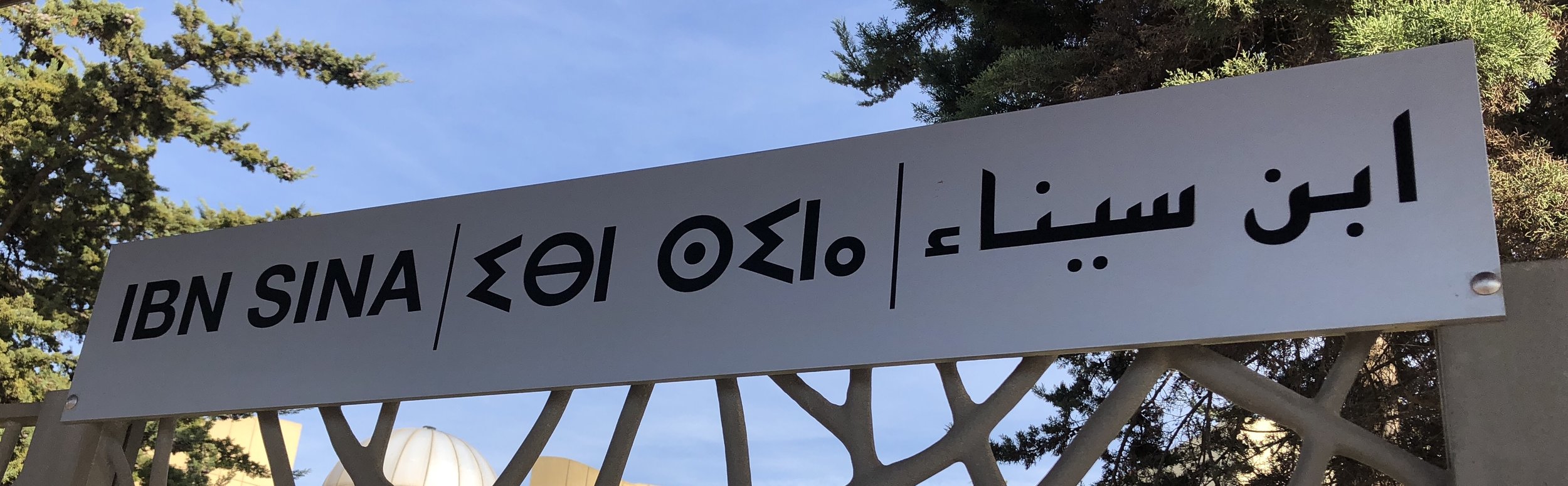

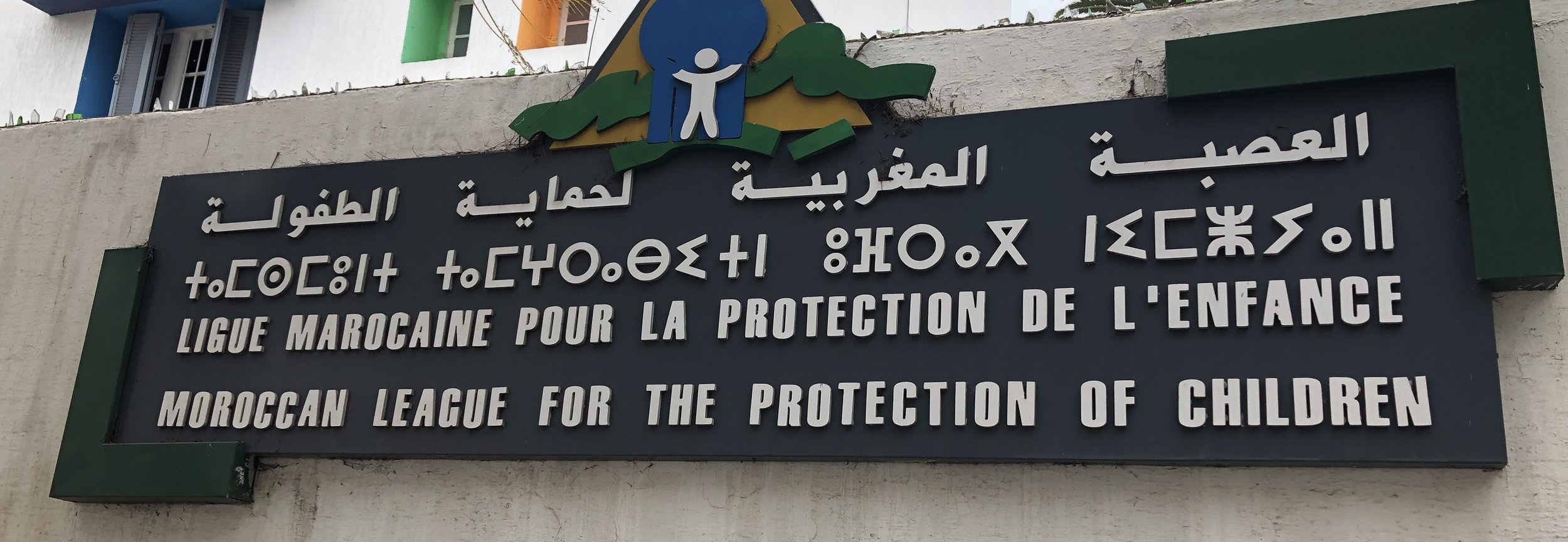

I fell into step behind Youssef and peppered him with questions about Toubkal, hiking, Berber culture. Toubkal is a popular destination and generally safe, but not everyone who attempts it is up for it, and not everyone who is up for it keeps safety in mind while hiking. He was kind of a school marm about safety, which was mildly annoying but totally understandable. Further up the trail, we heard helicopters flying overhead and then encountered several military escorts who were accompanying the governor of the province on a walk down from the refuge, where his helicopter had deposited him. The official visit to the mountain was meant to send a public signal about safety protocols and make sure that the guides (some certified, some not...) and hikers on Toubkal are following best practices.

Hey, governor!

While the icy, steep slopes weren't yet underfoot (and were, frankly hard to imagine in the dusty heat of the lower valley) Youssef told me that in recent weeks one hiker had died on Toubkal and another had fallen down a steep slope, breaking and dislocating bones and requiring a medivac helicopter. They were separate incidents, but shared the common thread of being avoidable and caused by willful, overly confident mistakes. It had been months since I was in tip-top Himalaya fitness, and I was constantly assessing my readiness for the terrain ahead, and calibrating my preparation against the other hikers we encountered.

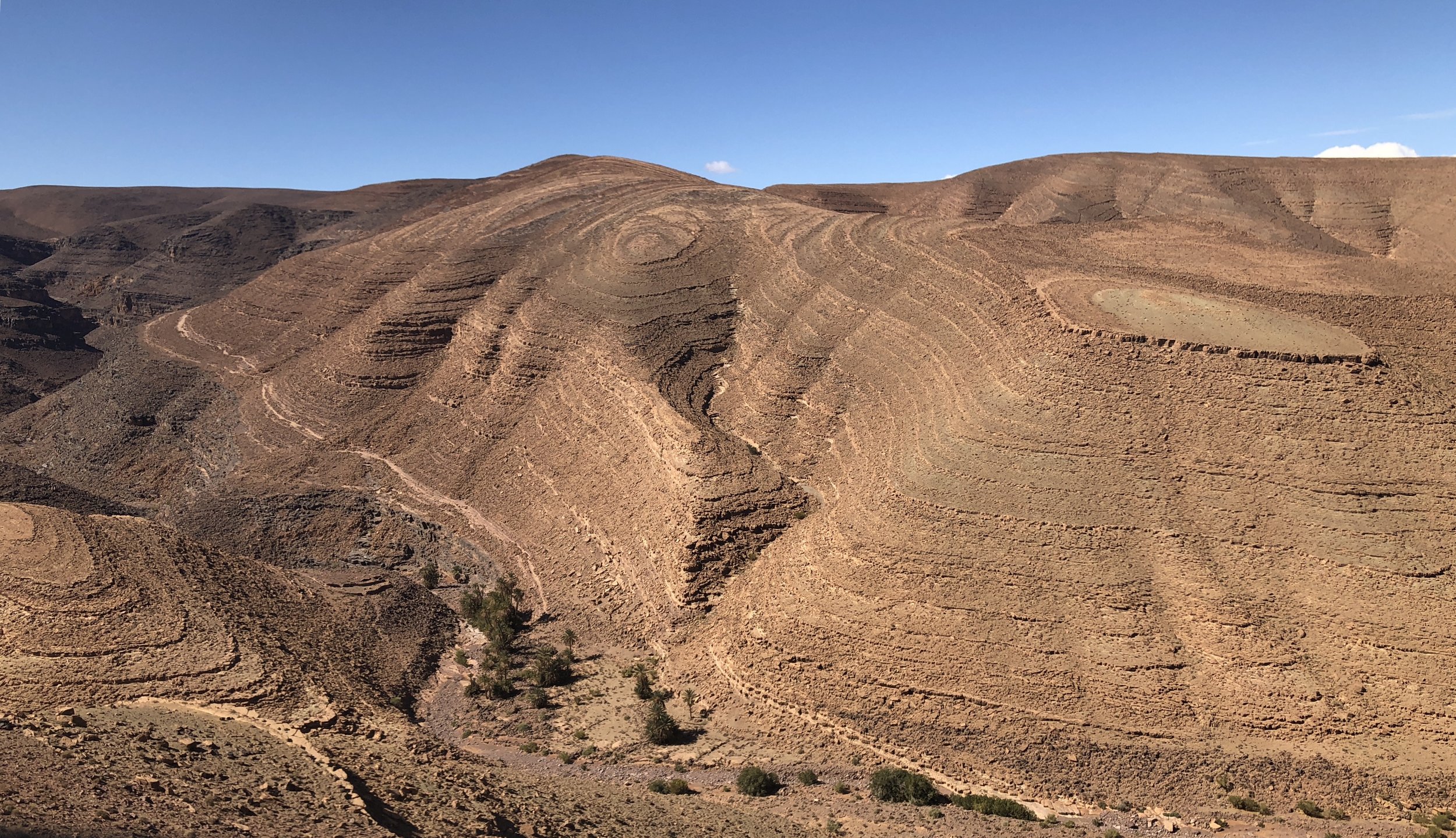

Patches of snow made an appearance a mile or two from the refugio and then spread steadily to cover the parabolic slope of the valley. The sun still felt warm in the clear skies, and the afternoon had a feeling of spring skiing. My refugio expectations were keyed to the experience Liz and I had at the "git" in Ait Aissa in February -- I was prepared for cold, uncomfortable, Type 2 Fun accommodations. Instead, the April-at-Sugarbush vibe prevailed, and we walked into a massive stone and timber dorm that wouldn't look out of place at ski resort in the States. We joined other hikers in the small dining room, and wolfed down the popcorn, cookies and mint tea that the muleteer served up. The sun was passing behind the mountains, and the temperature dropped fast in the expanding shade. Youssef dislodged us from warmth of the fireplace to give us a crash course in ice axes and crampons. This is what we came for!!

I purchased hiking boots at the Decathalon sporting goods store in Marrakech a few days before this trek, and I could feel hot spots on my heels warning of the blisters to come as we walked outside with our gear. I had walked approximately 20 feet in these boots up and down the aisle of Decathalon's shoe department before starting out that morning, but I silently thanked myself for risking new boots while Youssef tore into Tom for wearing trail running shoes. They were fine for the terrain we covered today but they spelled doom, apparently, for tomorrow's climb and made the crampons fit poorly. Mind you, Tom's trail runners were more substantial than the ones I would have been wearing had I not opted for boots... Youssef criticized my hiking pants for having loose cuffs, a tripping hazard when snagged by the cleat of a crampon, but was satisfied when I assured him I had gators -- a last-minute piece of equipment that an American friend in Marrakech loaned me with the assurance that I would not need them. Whew, dodged that! Back in the dorm, Tom, Tayla and I hunkered down with a few other hikers we'd just met and tried to figure out, have we unwittingly gotten ourselves in way over our heads with a mountaineering challenge that we're laughably unsuited for?

The next morning we started before dawn, headlights illuminating the icy snowfields around us. We started up, up, up, each of us cocooned in layers of clothing and our own quiet beams of light on the trail. The crampon cleats made a satisfying crunchy, slicing sound with each firm footstep, the metal blades cleaving evenly through the surface and creating a firm hold on the narrow single track through the snow. I talked to myself as we trudged uphill, thanking my hands for staying warm so far, thanking my boots for their traction despite the blisters, and reminding my lungs that no matter how hard this feels, it's worse for Tayla. She of the incredibly stiff upper lip, Tayla had been suffering with food poisoning from the moment she woke up the previous morning in Marrakech. She barely mentioned how miserable she felt, and was unwilling to abandon the goal, and so on she hiked despite bouts of skitters and upchuck.

We couldn't see the sunrise from inside the bowl of high peaks, but we watched the sky transform from ink to pale blue and paused to take it in. The next long stretch of the hike covered an open, icy snowfield that kept climbing up, till we reached the edge of the snow just below a ridgeline. We stopped here to take off our crampons and the sudden loss of awesome cleat-powered traction had me stumbling and sliding in the rock skree and loose dirt. The ridge formed a shoulder that led to the final ascent up to the summit, but from here we could already enjoy a commanding view of the Atlas Mountains -- infinite peaks that pierced the low clouds and left us breathless, literally and figuratively.

The summit of Toubkal, when seen from the trail just below it, is made of long, rounded rocks stretching upwards to the official top of the mountain. The trail threads through rocky passages and curls counterclockwise up to the top. Toubkal's distinctive summit marker is a massive triangle perched on stilts, an unmistakable sign that you've made it. We grinned, took photos, scarfed down trail mix and sat in happy satisfaction with the accomplishment. So fantastic!

Sitting at the summit, we could see forever in every direction, and I could just barely visualize some of the long-distance treks I had read about, weeks of point-to-point walking and climbing over mountain passes and through shaded valleys, eventually crossing this summit and continuing onward. My short, short time on Toubkal primed my fantasy of coming back to the Atlas Mountains for a BIG hike someday. For now, I have good memories, and even gained a friendship Youssef despite his insistence on doing everything by the book, and left the mountains feeling grateful for the experience there.

[Mt. Toubkal, March 26-27, 2018]